Visiting the Gillioz is a sensory experience. Settle into a seat, and you can almost hear the melodious plunking of the house Wurlitzer, the centerpiece of the 1926 grand opening. Run your hands down the gleaming banisters and you’ll feel the elbow grease that went into the theater’s restoration. Attend a jazz concert or a taping of The Mystery Hour and you’ll see the occasional wide-eyed youngster cultivating an appreciation for the performing arts. With a little imagination, it’s easy to picture the Gillioz as a stately 92-year-old gentlewoman, draped in Old World splendor and telling wry tales of the time she met Elvis Presley. The Gillioz has a heartbeat, and the community is listening—but that wasn’t always the case.

Arts & Culture

After 92 Years, The Historic Gillioz Theatre Looks Better Than Ever

As the Historic Gillioz Theatre nears its centennial, we reflect on the past, present and future of one of downtown Springfield Missouri’s crown jewels.

By Lillian Stone

Jun 2019

The Legacy of The Gillioz Theatre

The Gillioz Theatre opened its doors in 1926. Built by well known developer Maurice Earnest Gillioz, the theater’s opulent Spanish Colonial Revival architecture drew widespread acclaim, drawing locals and visitors to take in live entertainment and talking pictures. Word of the Gillioz’s splendor and inimitable service traveled along Route 66, and the theater eventually hosted three movie premieres, drawing celebrities like Ronald and Nancy Reagan—and even Elvis Presley, who sneaked away to catch a flick between concerts at the nearby Shrine Mosque.

The theater remained a Route 66 landmark throughout the Great Depression and World War II, hosting community songfests to raise morale. Several decades later, in 1970, customers left downtown in droves in favor of Springfield’s suburbs. Dust settled over the Wurlitzer, and the Gillioz began to fall into disrepair. The doors were closed in 1980.

Fast forward to 1990, when a group of community arts advocates—Nancy Dornan, Sam Freeman and Jim Morris of Morris Oil, to name a few—banded together to preserve the theater’s identity. The group launched a rigorous fundraising campaign, forming the Springfield Landmarks Preservation Trust and purchasing the theater. At the same time, the Gillioz was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The partners then began to restore the theater’s physical splendor—a project originally quoted at $1.8 million and concluded at nearly five times that amount. The doors re-opened in 2006, 80 years after the theater’s grand opening. Both new and returning visitors marveled at the restored details—the twinkling chandelier, the impressive replica of the original marquee, the large stained-glass window in the upper façade and the elaborate plaster friezes just outside the front door. The grand dame was ready to entertain once again.

Growing Pains for the Theatre

Unfortunately, after the rehabilitation was complete, the theater’s identity became murky. Executive Director Geoff Steele reports that, for several years, the Gillioz catered to a rowdy college crowd and kept the lights on using beer money. Physical damage and financial instability ensued. “Catering to one demographic—be that college students or baby boomers—simply isn’t feasible for a house this size,” Steele says, explaining that the Gillioz has a total seating capacity of 1,015. The Gillioz stayed afloat thanks to benefactors including Robert Low of Prime, but the theater needed a long-term plan. That’s where Steele came in.

Today, Steele runs the Gillioz alongside his associate director and wife, Joy Bilyeu-Steele. The couple is incredibly well suited to run an entertainment venue. Steele came up during the Christian music explosion of the early 1980s, touring as a tech out of Nashville and working for a record company. Bilyeu-Steele is a product of the legendary Bilyeu family—a bloodline that’s produced nine generations of musical southwest Missourians, most notably launching the Baldknobbers variety show in Branson.

“I got to the bottom of the stairs and I looked around… and I remember vividly thinking, ‘Man, I could fix this.’”— Geoff Steele

When Steele was tapped to lead the Gillioz, it didn’t immediately seem feasible. Steele had just paid off Remington’s, the south Springfield entertainment venue that he ran for 11 years. Still, he got the call from Gillioz Board President Philip Rothchild, who sought Steele’s leadership through the rocky period. The timing turned out to be impeccable—Steele had seen the Marshall Tucker Band perform at the Gillioz about a month prior to Rothchild’s call. “I remember walking out during intermission and walking down those stairs,” Steele says. “I got to the bottom of the stairs and I looked around… and I remember vividly thinking, ‘Man, I could fix this.’” He and Bilyeu-Steele agreed to take the reins, discovering their ultimate vocation in the process. “We got the keys, we walked through the theater, and we came up onstage,” Bilyeu-Steele says. “I just started crying. What a moment.”

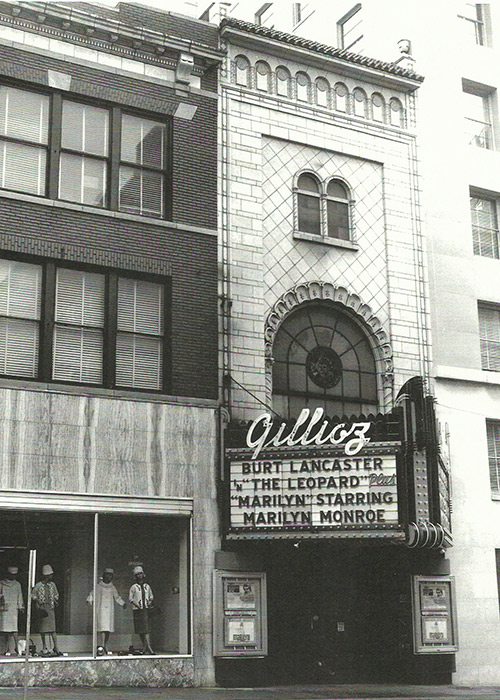

In 1963, the Gillioz’s marquee looked a bit different, with an elegant script for the theater’s name, and a bit more space to advertise the shows going on inside.

The current marquee at the Gillioz is a replica done in the style of the original, with plenty of glitz in its twinkling lights.

Perception Shift in Springfield

When Steele accepted the job, he knew the Gillioz needed a massive overhaul, both aesthetically and philosophically. So he started small by professionally cleaning the carpets and personally changing every burned-out lightbulb in the building—including more than 300 burned-out bulbs in the marquee. “Then, we changed the script,” Steele says. “We added the word ‘historic’ to the theater’s official namestyle. Now, when someone calls, we say, ‘Thanks for calling the Historic Gillioz Theatre in beautiful downtown Springfield, Missouri.’”

For Steele, changing the language is a key part of what he calls “cultural architecture.” It’s a way of going beyond the day-to-day operations to change public perception of the theater. That includes interactions with performers. Today, Steele prides himself on a safe, pleasant, above-and-beyond experience for all performers. That reputation has allowed the Gillioz to book bigger acts like John Mulaney, Lake Street Dive and Branford Marsalis—the latter of whom, widely considered the top jazz musician on the planet, will perform at the Gillioz in October.

The cultural architecture is also informed by community partners like The Mystery Hour and the Springfield Regional Opera, both of which work to improve perception of Springfield as a whole. “Jeff [Houghton] wants to export Springfield, and so do I,” Steele says. “There are names in entertainment that are singular. The Ryman in Nashville. The New York Met. Austin City Limits. The Fillmore in San Francisco. And my desire is to do that in the Midwest.”

“Twelve years ago, we weren’t even open. Ten years ago, we were bankrupt. Today, we’re a top venue with an Academy of Country Music nomination. I’ll take that trajectory.”— Geoff Steele

Giving Back to the Community

For Steele, preserving the theater’s legacy is only part of the job. “As a nonprofit, we have a twofold mission,” Steele says. “First, to preserve the historic theater. The second part of our mission has just come into play in the last four years: to go beyond preservation and enhance the quality of life for people in the Ozarks—visitors and residents alike—through arts education and entertainment.”

That mission is steadily being realized; in 2017, the Gillioz leased the third floor, formerly occupied by the Ozarks Technical Community College Fine Arts department, to Hill City Church. Now, Hill City has partnered with the Gillioz to open the space up for other nonprofits in need of office space. The incubator has been dubbed the For the City Center.

The Next Chapter for the Historic Gillioz Theatre

While Steele and Bilyeu-Steele have certainly taken the Gillioz to the next level, the work is far from over. “[Theaters like the Gillioz] are America’s Sistine Chapels,” Steele says. “Buildings like these simply aren’t being built any more. When we lose one of these, it’s truly a loss of part of our identity.” Like other 92-year-olds, the Gillioz requires a bit more upkeep than she used to. Steele explains that the more shows the Gillioz puts on, the faster the theater wears out, making it harder to meet compliance standards that allow Steele to sign national acts.

For a nonprofit organization like the Gillioz, that level of upkeep is a major challenge. “We’re a 501(c)(3) that operates with no government endowments, no tax breaks,” Steele says. “As far as I know, we’re the only historic theater in North America that is operating just on ticket sales.” Steele notes that the Gillioz is always accepting donations, and he hopes to revisit the theater’s current defunct endowment fund at the Community Foundation of the Ozarks.

Although the Gillioz is in critical need of community support, Steele is optimistic. “Twelve years ago, we weren’t even open,” Steele says. “Ten years ago, we were bankrupt. Today, we’re a top venue with an Academy of Country Music nomination. I’ll take that trajectory.” For now, he’s working his way to the theater’s centennial and savoring every moment. “There’s a chapter in this book that’s being written that I get to be a character in, and I want it to be the best chapter of the book,” Steele says. “I want this to be the most colorful, adventurous, exciting chapter of the Gillioz story.”

“I want this to be the most colorful, adventurous, exciting chapter of the Gillioz story.”— Geoff Steele

In the meantime, the Gillioz’s heart keeps beating. The sets are cleared, and the lights go down after each show, but you can still feel the history. It’s in every detail, from the delicate cherubs at the front entrance to the elaborate Proscenium arch to the vibrant blue “G” in the center of the theater’s sparkling stained-glass window. She really does look great for 92.