What it Feels Like

We found 417-landers willing to tell their stories of surviving a plane crash, looking at the earth from the quiet of space, holding on for dear life to a bucking bull, nearly facing death in the line of duty and so much more.

By Ettie Berneking, Matt Lemmon, Rose Marthis, Savannah Waszczuk | Photos by Brandon Alms

Nov 2015

Some experiences are just so extraordinary, we can’t do them justice except by giving a voice to the men and women who faced them. We found 417-landers willing to tell their stories of surviving a plane crash, looking at the earth from the quiet of space, holding on for dear life to a bucking bull, nearly facing death in the line of duty and so much more. In their own words, we share their moments of terror, and their moments of sheer joy. Their moments of doubt, and their moments of steely resolution. Read on, and be inspired.

Click through to learn what it feels like to...

Be Shot While on Duty | Find your Daughter After 43 Years | Be Santa Claus

Compete on American Ninja Warrior | Ride a Bull | Survive a Plane Crash | Be Addicted to Meth

Act in a Horror Movie | View the Earth From Space

Be Trapped on the Side of a Mountain After a Huge Earthquake

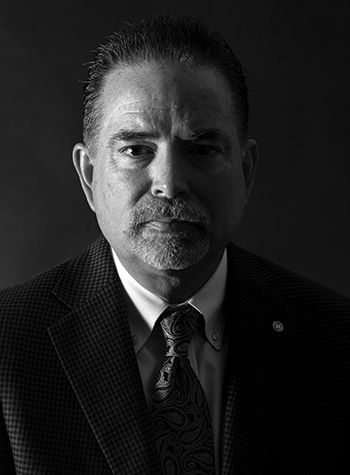

Since being shot in the line of duty in the early morning hours of January 26, 2015, now-retired Springfield Police Officer Aaron Pearson has had a monumental recovery. Thanks to first responders, surgeons, therapists and a host of other supporters, Aaron has made an incredible physical recovery (as you will read here). A good deal of his remaining problem stems from aphasia, or trouble saying what he really means to say. His wife, Amanda, who has been by his side every moment since the shooting, helps him during interviews and contributed significantly here, though the article is from Aaron’s point of view.

By Aaron and Amanda Pearson as told to Matt Lemmon

I remember the call came in just a little after 1 a.m. It was for suspicious activity and a “check person.” We caught up to the car near Glenstone and Chestnut. It had multiple people in it. The last thing I remember is seeing a guy walk away from the car. I took my eyes off of him to check the other officer, to see if one of us should run after him. The man wasn’t too far away from me. But I didn’t even get a chance to chase.

Officially, I was shot at 1:23 a.m. I remember at some point people trying to talk to me. I remember [SPS Police Chief] Paul Williams. He was going to talk to me, but I couldn’t talk. After that I don’t remember anything.

It was disorienting. I remember bits and pieces. I followed something with my eyes. I gripped somebody’s hand, which was a big deal because for a minute there they didn’t know if I would move again. There were pricks under my fingernails. They told us my bone flap [of skull that had disappeared] would come back. I didn’t even know I had a new eye until they told me, and I remember crying when they finally told me that. I started trying to walk.

I saw my kids 11 days later, when I was still in the ICU. My son Jack, 4, was a little distressed. I remembered (my 8-month-old daughter) Jovie’s name. Later, I was able to ask for Jovie again, and I just held her.

Originally they told us I’d be in inpatient care in Springfield for six weeks, but after just three weeks I was sent to Shepherd Center, in Atlanta, for rehabilitation. I thought I’d only been in the hospital one or two days. It seemed so soon. They cleaned me off the meds that were making me foggy and I really started to wake up, but there was more pain. I had a pretty bad headache for a while, but got off of the pain meds pretty quickly. Now I don’t take any. I don’t want to try them anymore.

I was really weak, but still trying to do new things. I wanted to try as much as I could. The therapists knew I’m really hard on myself, and over the weeks they would show me assessments from previous sessions to show my progress. I didn’t believe anybody. I had to see it on paper to believe how much I was improving.

I was so happy to get out of Atlanta, home to our house, kids, and the dogs. I’ve had my 180-pound Great Dane, Moose, since before we were a family. It’s just nice to be back to a place where I can go to sleep again.

Physically, I’m strong. I’ve always liked to train and bench, do CrossFit. The guys on my squad tell me that’s the only reason I made it through all of this, because I was, in their words, “such a beast.” I used to work out at the SPD gym, but now I go to CrossFit Springfield. Just last week I put up 315 pounds three times and set a gym record. The most I ever did was 385. At first, my injury scarred up so much that the scar tissue fused my jaw bones; they literally had to break it up. I couldn’t eat much. Now that I’m through that I’m eating all the time. After the incident I was down to 199 pounds, but now I’m back up to 240.

I’ve started playing golf again. When I was in Atlanta, I stunk. I have one eye, I couldn’t hit the ball. But now I’m trying; Rivercut and

Island Green are two of my favorite courses. It helps to have the normalcy, to take the kids to preschool and daycare, and to have a hobby like golf. We thought I’d get to drive again. I was looking forward to that independence, but I’ve had a couple of seizures. I’m going to be on seizure pills forever. Oh boy, good times.

I have a different perspective on life now, not working anymore. I’m enjoying life and trying to make the best of it. I’m still welcome at the PD, and let myself in with my ID card. I enjoy spending time with my squad. They’re good friends to me.

Still, my dad was police for 32 years, and Amanda’s dad is a police officer. So it’s still a little weird that I’m done at age 31. It’s like, “Okay… what exactly does that mean?” I’d love to go back to work, but right now it’s not something that’s in the cards.

I feel bad because, at the time, I didn’t know the community was doing so much for us. Everyone is so nice. One of my first trips out was to the UPS Store. I was just standing there, and this guy was being really perky toward me. I wondered, “Why is he acting like we’re best friends?” People still have their blue lights on. They stop to say they’re praying for me, or about this or that fundraiser. I don’t feel burdened. I just feel like I need to dress up a little more.

We started a “give-forward” site to help give back and are thinking about some sort of scholarship or first anniversary “thank you” event. And that’s part of why we do all of these interviews, to get it out there that we are thankful.

This summer we went to the National Law Enforcement Memorial in Washington, D.C. The fallen officers are listed in alphabetical order by department, and there was nobody there from Springfield. It was so close. I look forward to the day when this isn’t a story anymore, but if they’re still talking about me, then nothing else has happened.

After giving her daughter up for adoption at the age of 20, Carolyn Bledsoe and her sister, Mary, spent more than 40 years trying to find her. Little did she know, the two were living in the same town the whole time.

By Carolyn Bledsoe as told to Ettie Berneking

Carolyn Bledsoe was 20 years old when she gave her daughter, Robin, up for adoption. Carolyn worked to find her for more than four decades, but it was Robin who found Carolyn 43 years later.

Fifty years ago no one talked about anyone who got pregnant without being married. It was just shoved under the carpet. So when I found out I was pregnant, I told my parents, and they found a place in Kansas City—a home for unwed mothers. Only my sister, Mary, knew where I was. I was 20 and was there seven-and-a-half months.

The last day I was there, the nurses kept asking if I wanted to see my daughter before she was adopted. I unwrapped her, took my hospital gown off and held her to my skin and loved her. I whispered to her that I loved her and would find her one day.

I came back home, and the next year I don’t remember much. I was so traumatized by not being able to bring her home with me. But then I brought myself out of it, met a guy, got married and had three sons. My sister and I had always talked about finding my daughter. I was born with heart defects, and I wondered if she had them, too. I didn’t know if she was okay or if she had lived. Even though I had three other children and loved them dearly, that piece was missing.

My sister and I looked for Robin for 43 years. Then one day I was getting ready for a valve replacement. I didn’t have good odds of making it through the surgery, but I knew I would die if I didn’t have the surgery. So I prayed to God and said all I want is to know if my daughter is alive. I didn’t need to meet her, I just wanted to know. I left it with God, and I learned later that about the same time that Robin had this burning desire to find her birth parents.

It turns out, Robin had been adopted by a couple in Springfield. Her folks ran Springfield Seed and Floral downtown on St. Louis. That was where my dad went every spring to get his seeds. I remember going with him and seeing this little baby playing in the back. There she was, and I had no idea.

So I was preparing for the surgery, and I was sitting in the living room and the phone rang. I said hello, and she asked, “Is this Carolyn?” I said yes. She asked if my maiden name was Alexander? I said yes. There was a pause, and she said, “My name is Robin, and I’m the baby you gave up for adoption.” I started screaming. It was such a miracle. There was no contact, nothing, and suddenly she was on the phone.

We talked for about an hour and a half. I remember asking Robin to tell me everything she had ever done. It was just surface-y things, trying to feel each other out. I didn’t want to interrupt her life, so I was hesitant about what to ask. I wanted to ask when she got her first period, what color her bra was… all those little details, but I didn’t want to embarrass her.

After I hung up, I drove over to Mary’s. She was almost more determined to find Robin than I was. Lord, she came up out of her chair, and we were hugging and kissing and crying. She kept asking when we were going to meet Robin. She wanted to hug her and see her.

Here’s what happened next. We met at Robin’s house. She opened her front door, and we both said, “Oh my God, you are beautiful!” It was all hugs and crying, but I felt really calm and comfortable. I just wanted to see her, know what she looked like and to smell her and touch her.

After we knew each other three or four months she got out her baby book, and there was this picture of the day her parents had brought her home. It was the exact image I had carried in my mind for 43 years. There she was—the baby I had given up. I just cried and cried.

In 2014, Alan Cyr spent November and December enjoying visit after visit with hundreds of smiling children as Silver Dollar City’s Santa Claus. Learn what it feels like to be the jolly man in the red suit, and why Cyr says he’s more than excited to play the role again this year.

By Alan Cyr as told to Savannah Waszczuk

Like a best friend

“It’s funny, because some kids won’t tell their parents what gifts they hope to get; they just want to tell me. After the kids walk away, I’ll have parents come up to me and ask what the kids want, because they don’t have any idea!”

Like a movie star

“Oh yes, I look like Santa Claus. I have rosy red cheeks and a big white beard. When Thanksgiving comes around, I can hardly go into stores or restaurants. The children just know they’ve had a sighting when they see me out and around.”

Like a counselor

“I have about 95 percent good stories, but I do have some bad stories and some sad stories, too. I always try to be mindful of children and their experiences. Sometimes, they ask me things that I just can’t perform. A lot of children trust Santa, and they feel like they can talk to him, and they do. And some of these kids are really in need to talk to someone. It’s been great to be able to help them out, even if it’s just by listening.”

Like I’m scary

“You never know what the next child is going to bring. Sometimes it’s happiness, but sometimes it’s fear. They’ll come up to me, and they’ll sit on my lap, and they’ll just start crying. They probably think, ‘What’s happening? Who’s holding me?’”

Like it’s Christmas… every single day

“The kids bring me a lot of gifts. Drawn gifts, or sometimes even sewn gifts, like scarves. You can always tell when the kids make them themselves, and those are the really heartwarming ones. And what’s funny is when they bring me lists. They’ll bring me lists with sometimes 20 items on them! We’ll go through it, talk about it and then I’ll save it in a bucket next to me.”

Like I’m a little out of touch

“I was really amazed at the amount of electronic equipment these children want and need these days. I say need, because they actually believe that they need these things! I get requests for iPhones and Nintendos and all these things I’ve never heard of. Usually, I’ll say ‘If the electricity went out and you had to go to your room, what would you want to play with?’ And sometimes, I’ll get nothing but crickets!”

Like I’m lucky

“When I was given this opportunity, I knew it was something I could not turn down. I love to see the smiles on their faces. I hope that I can help a child through a problem or help them with their happiness. I’m glad to be a part of it.”

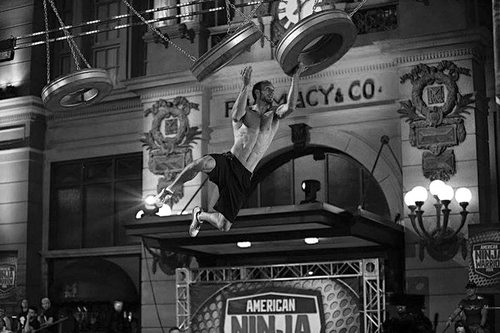

In 2014, Adam Arnold of Springfield was a walk-on at the St. Louis filming of America Ninja Warrior, but he went out in the city finals on the rumbling dice. He came home and designed a 12-by-16 workout station with 20 obstacles on it so he could train to try and do it all again—but even better. After attempting and failing to audition for the 2015 Kansas City course, he immediately drove to Orlando to try yet again. He was able to walk on, and he was one of only two people to finish the course that night.

By Adam Arnold as told to Matt Lemmon

This year, I went to Kansas City and waited for six days, but I didn’t get there soon enough. I didn’t get to run [in the American Ninja Warrior obstacle course], and I immediately drove to Orlando. I quit my job. It was also during finals week. But one of my teachers at OTC, Dwight Chism, is a fan of the show and moved a final for me. Because of him, I was able to go.

When I got to Orlando, I was number 15. I waited 12 days, but I got lucky. The producers knew I had been in KC and liked my dedication. They bumped me to number eight. Filming runs overnight, so I got to run about 9 p.m.; I was one of the first people to go.

I was very excited when I started. I had waited so long, but knew the wait was finally worth it. I wasn’t worried about the obstacles—except for the rolling log. It’s insane. And sure enough, while I was on the rolling log I could feel my grip start to slip. The G-force threw me off, but I got lucky and landed on the mat. I don’t know how I didn’t get whiplash.

It was after the salmon ladder that I knew I would make it. When I completed the last obstacle, the invisible ladder, to be honest, I don’t really remember what was going through my mind. I was looking out to the sky, and it was so dark and black. I saw the stars. I got my feet up, and I crawled my way to the button.

To hit that button and finish was mind-blowing. It didn’t hit me until I looked down and saw everyone cheering for me. I remember breaking down and covering my face, and I started crying and thanked God for giving me the strength.

It’s hard to think that I’m a “reality TV star.” I just feel like an average person. I like getting involved with kids, and maybe giving them a reason to get outside, away from TV, get them climbing and more active.

Adam Arnold in action at the American Ninja Warrior finals in Orlando.

Luke Snyder rode a lot of bulls in his 14-year career with Professional Bull Riders—during which time he won five event championships, qualified for the World Finals 13 times and was crowned Rookie of the Year. When you’re a 155-pound guy on a 2,300 pound animal, sometimes you win, and sometimes you lose. Sometimes a loss involves breaking your neck. Luke shares how he was just as nervous for his last bull as he was his first, and how a ride can prove to be the slowest eight seconds of your life.

By Luke Snyder as told to Rose Marthis

BEFORE THE RIDE

Bull riding is really easy to over think. A lot of guys think “Is he gonna spin left? Is he gonna spin right?” Your adrenaline is flowing as wide open as it can, so you take a final deep breath, and when you nod your head, the gate opens. That first jump out of the chute, everything slows down. As fast as 8 seconds can go, once you do it a long time, everything slows down.

1 SECOND

The first move a bull makes is he’s gonna come up in the front end, and you want to get all your momentum moving forward with him, so you don’t get rocked back on your pockets. The second jump is when he does his big kick. That’s really crucial, because the first two jumps out of the chute can make or break a ride.

2–3 SECONDS

You want to be in a good position, because on the PBR level the top bulls are either gonna spin to the right or spin to the left, and they’re gonna do it in the first two or three seconds. You’re thinking to yourself that you want to stay really square and you want your weight evenly distributed on both legs, so if he goes left you’re ready for that, and if he goes right you’re ready for that.

4 SECONDS

Now he’s probably spinning. You’re working on your moves. You want to make sure your free hand is correcting and putting your body weight in the right position. You just want to stay ready for anything. You don’t want to be thinking to yourself, “The whistle’s coming, I’m halfway there.” You want to ride through eight seconds, making sure you’re there for the qualified ride.

5–7 SECONDS

By this time you know it’s getting closer, so you’re turning on the afterburners. You’re really putting all the gas out there now. You’re scrambling, you’re making moves with the bull. You want to stick with quick little aggressive moves with your free arm so you’re really trying to keep your center of gravity right in the middle of the bull’s back.

8 SECONDS

You hear the whistle blow, and it’s time to start looking for a place to dismount safely. Once the bull fighters have the bull’s attention, you’ll look and try to find a safe spot, and use the bull’s momentum when he kicks to sling you as far away from him as possible. Then look for the nearest fence and crawl up on it. You act every time like there’s a bull right behind you. That way you never get run over or hooked.

AFTER THE RIDE

Once you get to safety, you check your surroundings and make sure you’re alright. When the bull leaves the arena, you listen and wait for the judges to score your ride. It’s just the greatest feeling in the world. It’s the ultimate adrenaline rush. “I just rode a 2,000 pound animal that was trying its darndest to buck me off.” The crowd’s standing on their feet, and your heart is about ready to beat out of your chest, and it’s time to celebrate.

On December 12, 2014, Integrity Home Care’s private plane carrying four employees hit a cell phone tower while 500 feet in the air. Roughly 30 seconds later, the plane lost all of its fuel and its engine shut off. It eventually crashed near downtown Springfield. Miraculously, all passengers survived. Hear the first-hand accounts for everyone on board.

By the pilot and passengers as told to Savannah Waszczuk

The Pilot: Bill Perkin

Vice President of Special Projects, Integrity Home Care; Owner, Perkin Marketing, LLC and Perkin Media, LLC

I had about 1,300 hours as a pilot at the time of the crash. We had flown this route, Kansas City to Springfield, six times in the past eight weeks or so. I was hoping to get back before dark, but we left late. We couldn’t see well when it was time to land.

We called to the airport, and we eventually decided to try and land at the downtown airport as originally planned. I spotted a familiar tower, and I thought “Well, we’re low, but we’re okay.” And just about that time, Greg said, “Oh, no.” I didn’t see it, but there was a cell tower in front of us. We caught the top two feet of its lightning rod.

At first the engine was still running and we kind of recovered, and I got control of the plane. We could see the airport. I thought, “Okay, well, it’s running rough, but we can limp in there.” Then, in less than 30 seconds, the engine stopped. I remember saying into the microphone, “God help us now,” because there’s not a lot you can do at that point.

I think we all did a quick inventory check of ourselves then. We thought, “This could be it.” When you’re 400 feet off the ground, it’s dark and the engine is silent, short of a miracle, something bad is going to happen. As a pilot, my focus was “How can I get this plane down with the least damage?”

I know God had us under his guard, because I couldn’t have done it myself. We hit trees that slowed us down. We went over a house, and then our right wing caught a tree. That forced us down at about a 70-degree angle, and the plane spun around and backed in between a tree and a pole.

There were a list of things I’d count as miraculous in the accident, and it was the combination of them that allowed us to survive.

Greg Horton

CEO, Integrity Home Care

When we struck the cell tower, I was the only one who saw it coming. I barely had time to say “Oh, no.”

My mind started calculating all of the scenarios. I knew that it was going to hit our left wing and probably take it off. Then, in my head I could see us doing the death spiral that you see in the old war movies. There was that awareness that “this may be the end of my life.” A few seconds later our pilot regained control of the plane, and I thought, “Thank you, Lord. We’re going to survive.”

Just a few seconds later, the engine sputtered and died. It got really quiet in the cockpit, and that’s when I really had a chance to talk to God. My only question was, “God, are you sure you’re done with me? Because I didn’t think that you were.” I had talked to the Lord a couple times already that day, and I wasn’t concerned about my eternity, but I was surprised at the timing. But there was just a sense of peace in the whole plane. Nobody was screaming or frantic, and that’s pretty amazing.

I didn’t want to say anything to Bill to distract him. I just sat back in my seat. Shortly after, I saw treetops hitting the wings, and I knew we were going to have impact. I breathed the name of Jesus thinking that may be the last word I said, and then we had a tremendous impact. We started spinning and tumbling, then there was a light bump and we were sitting upright. I was staring at lights out of the cockpit, and the plane was on the ground.

Time went fast, and yet it went slow. There was a feeling of total helplessness, but also a total dependency upon God, because I knew there was nothing I could do about it except trust him. Whatever the outcome—I left it up to him.

![]() Amy Ford

Amy Ford

Executive Director of Home Health and Hospice, Integrity Home Care

I’ve never liked to fly. I’ve always had a fear of it, and I’ve always given Bill a hard time, saying, “There’s no way I’d ever do this with you.” But this was a short trip up and back, so I thought, “Okay. One time. It’s not going to hurt that bad, right?”

After we struck the tower, we thought there was a chance we would still make it to the airport. But soon after we could see something falling out of the left wing. Within seconds the engine died, and I realized we were going where we were going, and we didn’t have long to get there.

I resigned myself to the fact that it probably wasn’t going to turn out well for any of us. I said a short prayer, and oddly enough, I felt at peace. I am young, and I have a young family—I have a son who just turned 3 and a daughter who just turned 2. I thought about how close it was to Christmas, and how it was going to be a sad day for my family.

Then my thoughts went to my husband and children and how this would impact their childhood and the rest of their lives. The thoughts were extremely emotional, because no mother wants to think about their children growing up without them. As difficult as these thoughts were, I knew my husband would take care of them, and I knew he would keep my memory alive.

I always thought that this type of situation would create great panic, but that wasn’t the case. Not a word was spoken, and there was a very peaceful feeling in the plane. Maybe we were all just saying our special prayers, but we were all calm.

There was a feeling of restraint due to my seatbelt, so I took it off, reached out and held Paul’s hand and waited for it all to end.

![]() Paul Reinert

Paul Reinert

Chairman and co-owner, Integrity Home Care

I was in back of the plane on the left side, behind the pilot. I knew the airport was close. We were just going along, and then I heard Greg yell out, “Oh, no,” and there was this big, loud abrupt noise.

I looked out of the plane, and I could see gas was coming out of the left wing, and parts of it were falling off. Yes, I was concerned. But I wouldn’t say my life was flashing before my eyes.

After the engine died, Amy looked at me and said, “What do we do now,” and I said “We pray.” Soon the engine died. It was completely quiet, and we were right over the city. But I did not have a fear of death. I thought, “It looks like we’re going down, and I’ve gotta be prepared.” But I had confidence that Bill knew what he was doing.

At the time, we were angling down. There was this sequence of events and a loud noise, and then a violent vibration and rotation and another loud noise. Then we were sitting on the ground.

After we landed and learned we were all okay, Amy lunged over me to get out, and I got out next. In a minute or two, first responders were at the front of the plane, and I had an EMT assigned to me. I was in shock. I called my wife, and she came and picked me up and took me to the hospital.

Later reality started to set in. I know now that I could have died very easily, and so many things could have gone differently. My daughters who live in Colorado and Ohio said they needed to talk to me to know that I was okay, and my younger daughter was even home by noon the next day. I thought, “I wonder if it’s in the paper,” and when I picked it up, there it was in four-inch headlines. It was all crazy. I am so grateful of how things turned out. Every moment is sweeter now.

Anna Mason spent 22 years using methamphetamines. After 11 years of being clean, now she is helping other addicts kick the drug as a substance abuse counselor at Clarity Simmering Center, a Division of Burrell Health. Read what it’s like to tackle that monster.

By Anna Mason as told to Ettie Berneking

At 23, I was a single mom and was trying to keep up with my small business, and someone introduced me to methamphetamine. Before I knew it I was getting high every week. I told myself it was under control. I even remember keeping track—well I’ve only used for a year; well I’ve only used for two years. I used for 22 years.

From a clinical point, methamphetamines cause dopamine to be released, but 1,200 percent more than usual. Suddenly you have all this energy. You can take care of five kids, mow the yard, clean the house. Your heart rate is up, and you’re more alert. Eventually your body stops producing dopamine on its own, and you crash. There were hours that turned into days, and long eventful evenings where my brain was trying to out race my heart. The need to calm the nervous energy could lead me to repeating routine behaviors, whether wallpapering, painting, cleaning, all of which would feed the lie that I would tell myself: That this is all acceptable because I am being productive. Truth is, there would be months on end where there was no sleep, where words were difficult to pronounce because of the lack of care to myself. This ongoing isolation stole my family, stole my ability to interact with society and raised paranoia to a point of guilt, shame and embarrassment. This shame and guilt quickly became the anger that fueled all my relationships. No one would approach me, and it became obvious that without the drug, I was nothing but a shell of a human being. I was lost.

By this time, I had lost all my bottom teeth and a couple of my top teeth. My eyes were bug-eyed, and there wasn’t much muscle mass in my face. It eats you from the inside out.

Then they raided our house, and I was put in the drug court program and started going to treatment at what was then the Larry Simmering Recovery Center. I would stomp around, but those people would love me anyways. That made me really angry. How could they love me? I was mean, and I was ugly. I would think, “You’re a bitch, don’t love me.” I didn’t love me, and I didn’t want anyone else to care about me. That anger was the protective wall I had created to keep others at arm’s length because I was unable to admit to the chaos that had become my life. Then one morning, I was in the bathroom curling my hair, and I saw myself in the mirror. That was probably the first time I had seen myself in years, and I started bawling. I realized my soul was still alive. I had to get better and fix what I shattered over all those years.

I went back to group that day and talked to the ladies who had been so supportive. I apologized for being such a bitch, and then we got to work. We worked on anger and self-esteem, and I finally started to give a crap about me.

I’ve been clean almost 11 years, and I still continue to change.

After graduating from Central High School in 2010, Pfeifer Brown moved to Los Angeles to pursue a singing career. She found herself acting instead, and starred in the summer hit The Gallows. Brown shares how when you’re filming a scary movie in a scary place, you can get scared stiff.

By Pfeifer Brown as told to Rose Marthis

It was super-interesting, and honestly it had such a real feel as far as the horror genre goes because we were already filming in haunted places in Fresno, California. It was such a small cast and crew on set, we could count everybody that was supposed to be on set on both hands. So we would hear something up in the rafters of the theatre, and we’d look around, and every single person that was supposed to be with us was with us. So it was just constant fright and terror. Scary things were always happening, and we were filming overnight. We would film from 4 p.m. to 4 a.m., and it was just so real.

We had multiple things happen on set that were kind of freaky and paranormal and scary, and so those things just added to the terror of being on set. We also used our real names in the film so it was so natural that when we’d get thrown into a situation like being up in the attic, we’d be using our real names with each other. So if something scared me I would genuinely be like, “Reese, Reese!” It just felt so real.

The scariest thing that ever happened to me on set was the first time filming. Reese Mishler and I were doing a scene up in the attic, and this was when our budget was still super-super-tiny, so we had a handheld camera that we were using on our own. Chris Lofing and Travis Cluff, the directors, were down somewhere in another room in this theatre—an old, old, old haunted theatre. Reese and I were up in this attic all by ourselves with just a camera, and it was connected to something that the guys were watching downstairs. But we were up there alone, and we were going through the attic in this scene, but nothing had happened at this point to genuinely scare me. So I was like, “I have to stay in the zone because I’m acting. This is my job.”

But I remember Reese and I got to a certain point in the attic where we both just stopped because this weird feeling came over both of us. We knew we were working and we needed to be doing what the directors told us to and finish the scene, but we both got this real feeling and out of nowhere this voice just popped up between both of us, like right between both of our ears. It just whispered Reese’s name. And we freaked out.

He dropped the camera down, so it stopped filming but it continued to record, and we just sprinted as fast as we could out of that attic. There was no light, so we came out just bloody and bruised and scratched and just horrified. Just genuinely horrified. I was crying. Reese was crying. It was a disaster.

But after that happened, I mean I guess it helped since it was a horror film, but I was just very, very sketched while we were filming because I didn’t doubt that something creepy could happen again.

Ever since she was a little girl growing up in Carthage, Dr. Janet Kavandi had dreamed of going into space. Now the deputy director of the NASA Glenn Research Center, Kavandi has been on three missions to space, logged more than 33 days in space and traveled more than 13.1 million miles in 535 earth orbits. But no amount of stargazing would have prepared her for her first launch.

By Dr. Janet Kavandi as told to Ettie Berneking Photos courtesy NASA

Your chances of being selected for a mission are really small. I was sure I wouldn’t make it, but somehow they picked me. I still joke with the guys in charge of selection about them putting my name in the wrong pile. It was on my husband’s birthday when I got the call. I was speechless.

One exciting part of the process is waking up on launch morning. You put the suit on, and technicians have to help put it on you. They pressurize it and make sure the valves are operational. You walk out to the astro van, which takes the astronauts to the launch pad. There is a lot of press there taking photos, but the pad is very quiet. There’s no one out there. It goes from a big crowd of cheering people to very quiet with just the hissing of the gasses at the launch site.

You stand there and look up at the space ship and think, “Wow. We’re going to get into that.” You get in an elevator, ride up to the top of the launch tower, cross the walkway to the shuttle and get strapped in to the ship. All the other people leave, and you’re the only six or seven people in a few-mile radius. They start counting from mission control, and your heart rate goes up. The closer they get to 0, the faster your heart goes. You just hope they don’t cancel the takeoff. Six seconds prior to launch, they start the main engines, and you can feel that. Then at 0, the big solid rocket motors ignite, and that’s the signal you’re really flying to space because you can’t turn those off. You have to leave the pad.

It’s a lot of vibration and a lot of noise. It’s hard to focus on the controls, you’re shaking so much. There’s a big boom and a flash as the rockets detach, and then it’s very smooth and very quiet. For a minute you think everything stops, but you get heavier and heavier in your seat as you climb faster toward space until you feel like there’s an elephant sitting on your chest, the pressure is so intense. It’s hard to breathe the last minute. Then you’re in space, and you float.

The only thing holding you down is the seatbelt. Your legs and your arms float up. It looks like an IMax movie. The earth is very blue, and it is round. You can see storms forming and cloud formation. The view I enjoyed the most was at night. You can see all the city lights, especially in Europe. You can identify any major city in Europe just by the lights. Then you pass over a continent like Africa, and you pass over vast areas of darkness. Then you pass along a campfire, sometimes in Australia and sometimes in Africa, you know they have no idea you’re there. It’s just a really surreal feeling to know that humans are out there, but you can’t see them and they can’t see you. Another extraordinary view is the reflection of the moon- light on the ocean.

The most impressive thing of all was the way thunderstorms look from space at night. You can see the lightning and the way it travels. Especially over Africa, the storms are very intense at times. Lightning would travel hundreds of miles following a single cloud chain. It almost looks like popcorn—the big fluffy clouds light up from the inside.

Dr. Janet Kavandi sits in the commander’s forward flight deck station on her trip to space.

The whole time you’re up there, you’re always weightless. The only way you don’t float is if you strap yourself down. At night, I liked to put my sleeping bag on the ceiling or the wall because you can’t do that on the ground. It’s a fun brainteaser when you wake up. It’s disorienting. I would first wake up and look for the floor and the ceiling to get out of the bag the right way, but then you learn that you don’t need a ceiling or a floor, so I would float out of the bag and not care if I was head up or head down.

The suits come off right after you reach orbit. The big orange suits are only for emergency if you lose pressure in the cabin during ascent or descent. You wear normal clothing with Velcro on the pants so you can stick things to you like books, pens or eating utensils. Even your senses change as the fluids in your body distribute. You get more pressure in your head and get a sort of sinus stuffiness. It’s like having a cold where you don’t taste your food as well. People like spicier food and bring hot sauce and horseradish. On the shuttle especially, you almost always try to eat together. It’s fun. People will eat upside down or wrap their legs around something or hook their toes under a strap just to stay in place. If you want to share something, you just float it across to the other person.

You’re with people you’re really good friends with, and you’ve trained with these people for at least a year. You become a family. The only regret that you have is that you can’t show your family at home what it’s like. You wish you could hold them up to the window for just a minute to see what the world looks like from space.

On April 25, it was a normal day on a mountain. Dan Nash and his Satori Adventures and Expeditions team were eating lunch on Cho Oyu in Nepal, taking a break from their ascent. Then a 7.8 magnitude earthquake struck the region, and Dan scrambled for his life before spending the next few days living through the aftermath.

By Dan Nash As told to Rose Marthis

We had carried a load to Camp One and dumped it, and we had come back to Advanced Base Camp. It was our first load. Camp One is at 21,000 feet. We were eating lunch at about 1 p.m. Beijing time, because we were on the Tibet side. After we finished eating we were all just sitting and socializing. There were about six or eight of us in the tent. And then all of a sudden at about 2 p.m., we felt the earthquake.

The Earthquake

I’m not someone who has ever really been in an earthquake, so I didn’t really know what an earthquake felt like. I guess I always thought it was like a shaking of the ground, but that’s not really how it feels. It’s more of a rolling. It comes in waves. We felt this wave, and the whole tent and everything was shaking and moving from this wave, and we immediately went outside. The cooking tent was right next door to the dining tent, and we had all of our sleeping tents scattered around. The Sherpas, who were in the cooking tent, were coming out, too. I heard them say “Earthquake, earthquake!” That was really where it kind of clicked with me.

Honestly I didn’t really know what it was at first. It was powerful, and the waves kept on going, I’m going to guess it lasted maybe 45 seconds. It seemed like a long time when we were constantly getting hit by these rolls. They were big enough that I had to hold my arms out straight away from my body to balance myself so I didn’t fall.

So we were all balancing ourselves and going, “Holy cow... Earthquake, earthquake!,” you know, and we were all just kind of there. We had two New Zealanders in our group that had been in earthquakes before, so they immediately knew. I was the only American, everyone else in our group was from Europe, and then the Sherpas.

It was snowing, the clouds were hanging real low and everything was kind of gray and overcast. Above us was a huge serac, which is basically a huge block of ice that was coming down the side of the mountain. The serac was probably two lengths of a football field and probably 50 feet high. It was a long shelf of ice that accumulated on the ridgeline that was up above us. It was probably 600 or 700 feet above us up on the mountain, and it was probably a 30-degree slope up to that serac from where our camp was. Next we started hearing cracking. These huge, loud cracks of ice were coming from the serac. When you’re in the mountains and you hear ice cracking like that, it’s something you pay attention to, because that means avalanche, right? So we hear this cracking, but I couldn’t see the serac because it was snowing. Then, on the mountain that was directly across from us, this huge avalanche cut through.

The Avalanche

The avalanche on the nearby mountain was low, so I could see it. We saw all the snow and ice coming down the side of the mountain and into the glacier. Our attention went directly over there, because this avalanche was occurring over there, but we were perfectly safe because there was a glacier in between us. But next something started cracking above us again, and then all of a sudden I heard the Sherpas yell, “Avalanche! Avalanche! Avalanche!”

I don’t think anybody knew what to do immediately, but then all of a sudden everybody, at the same time, started running. We were just camping on rocks and snow, and there were big boulders that were scattered about. Some of them were the size of dining room tables, and some were the size of cars. Everybody started looking for a big boulder. I dove behind a boulder. Everyone was running and moving around trying to find some place to get to. I didn’t really see it because of the snow, and I was just looking to get somewhere safe, or somewhere I thought was safe. Then the snow started coming through as the avalanche was coming. The snow was sliding across the top of the rock and coming around the sides of the rock, and I was just huddled in this little space behind the rock. The snow was passing along the sides and over the top of me. Thank goodness it wasn’t any of the serac, because then it would have been chunks of ice. It was just snow from all the fresh snow we had the past few days. There were a few pieces of harder snow, but that was really it. And then it was just kind of over.

Next everybody started to stand up and look around. We were kind of in disbelief, and at the same time, we were thinking, “the serac didn’t come down. If it had come down, we would have all been dead.”

We had other teams on different mountains. We had a team at Mt. Everest, a team on Manaslu and a team on Ama Dablam. We called around to our other teams on the satellite phone, making sure that they were all okay. The Ama Dablam team was okay and the Manaslu team was okay. But the Everest team said, “Things are really bad here. Part of base camp is gone. There are people missing, and there are people buried. We think all of our team is here and accounted for, but the other teams have sustained injuries. There are people injured here, and there are probably people who have deceased.”

Getting reestablished

Next all the Sherpas started calling home to Kathmandu. Of everybody that was part of the Satori team, their families were okay, which was great, but many of them lost their houses. One of our main Sherpas was Mingma; I said, “Mingma, are you okay? Are you okay?” He was like, “Yes, my family is okay, but my house is broken.” So a lot of them lost everything they had. But their families were okay, and they were happy that their families were okay. So many of them, their families and their wives were just staying in tents in Kathmandu because their houses were just piles of bricks. They just set up a tent in the yard or the street.

Next we were in the position of “Okay, what are we going to do now?” The rest of the afternoon there were at least two more aftershocks that occurred. And again there was more cracking up above us. That night there was another aftershock, and I was lying in my tent thinking, “If that comes down, I’m done.”

The next day the sun actually came out and the snow quit, which was the first time in about a week and a half that it wasn’t snowing. Everything seemed to be more mellow, so we had a meeting with the Sherpas and everybody who was there. We said, “What do you guys want to do?” The Sherpas said, “Our families are okay, we want to continue to work.” I mean they need the money, right? Now they had to rebuild their houses. The New Zealand climbers didn’t want to go anymore, so they turned around and went back down and went home. Everyone else that was there wanted to keep climbing. There were eight expeditions on Cho Oyu, about 50–60 total climbers there. A few people from some of the other teams decided to pack up; they didn’t want to go anymore. But probably three quarters of them said they wanted to continue to go.

A Change of plans

At first we continued to climb. We moved up to Camp One the next day, or two days later. We took another load up there and started continuing our rotations. And then when I came back to ABC, the Sherpas said that the Chinese Mountaineering Association was coming up to base camp to talk to us all. That happened a day later, and the Chinese told us that they were revoking our permit. They were revoking all the permits on all the big mountains on the Tibet side, which were Shishapangma, Everest and Cho Oyu. They were basically sending us all home. Some people were upset and some people were angry a little bit, but most people, I think, understood that it was for our own safety.

Next came the problem of figuring out how we were going to get home. The border between Nepal and Tibet was completely destroyed. There were little villages along the way, and those villages were no more. They were gone. The Chinese military had secured the entire border. We couldn’t go back to Kathmandu, which is where all our flights were out of. The Chinese government brought some vehicles out to us, picked us up at the Old Chinese Base Camp, and drove us to a little town called Tingri. We spent one night in Tingri, they had these vans meet us and then we took a two-day drive to Lhasa. And then when we got to Lhasa we caught a plane to Beijing. And then from Beijing we could fly anywhere in the world, so I flew home. The travel home took a week, so it was a little, umm—adventurous—to get home. Three days of travel, just through the mountains.