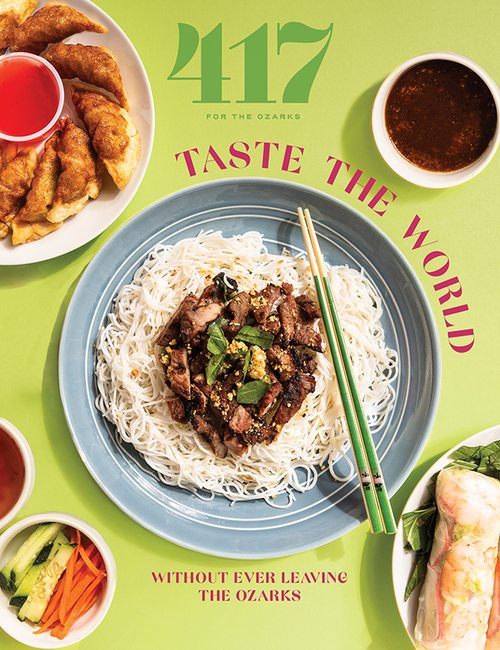

Health

Digital Doctors

Several local health care providers are using innovative services to bring care to all. The underlying concept behind the innovation: telemedicine.

Written by Lillian Stone | Illustration by Liz Leonard

Dec 2016

For many of us, a visit to the doctor’s office is standard procedure. However, thousands of people lack easy access to care because of location, physical ability and other circumstances. Several local health care providers are changing that by utilizing telemedicine, which brings patient to provider with a click.

Power to the Patient

According to Bridget O’Hara, product manager for CoxHealth, telemedicine is an opportunity to enhance patient-focused care. CoxHealth’s telehealth service, DirectConnect, started as an experiment in occupational medicine four years ago when an employer in West Plains wanted care for employees suffering workplace injuries. The expense of bringing a physical CoxHealth location to West Plains didn’t add up, so telemedicine seemed like a great choice to deliver care. CoxHealth now uses DirectConnect for a number of patient services, including employee health care. Employers are able to offer DirectConnect as an employment benefit, allowing employees to receive care without leaving the workplace. It’s also a benefit for part-time employees who don’t qualify for a company health insurance plan.

O’Hara estimates that, today, DirectConnect covers around 60,000 patients. That number is rapidly increasing: October marked the release of DirectConnect to the general public, making care faster, more affordable and convenient for patients with everyday ailments like sinus infections, sore throats or poison ivy. Those patients can connect with providers via webcam on smartphone, tablet or computer. A major plus: The service offers flexible hours for those who can’t make it to a doctor’s office during the workday. Patients can access care seven days a week with weekday hours covering 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. and weekend care between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.

“In the old days, you had doctors that came to your home to treat patients,” O’Hara says. “But this is really kind of bringing that back. You are able to deliver the provider to the patient’s home. That offers a huge convenience and huge savings.” Telemedicine also benefits the healthcare system, as it frees up Urgent Care waiting rooms for urgent cases and resolves minor ailments with at-home consultations. Providers can only bill certain patient insurance companies for telemedicine services, but DirectConnect visits are definitely more affordable than an out-of-pocket visit to Urgent Care—they cost roughly between $45 and $49 out of pocket.

Next on the agenda for CoxHealth is placing DirectConnect in schools. A grant from the Missouri Foundation for Health is going toward telehealth for six elementary schools starting in January. The service will hopefully impact students whose health needs have affected school attendance.

Facilitating Better Care

Angela Davison is a registered nurse and the telehealth coordinator for Citizens Memorial Hospital in Bolivar. According to Davison, Citizens Memorial has been building the infrastructure for telehealth since 2006. Today, the hospital has 24 mobile units, known as telehealth carts, throughout the service area. The carts are placed in long-term care facilities, rural health clinics and several other specialty clinics. Eventually, Citizens Memorial hopes to make telehealth available to qualifying patients through a mobile app. For now, the mobile app service is mainly used for internal hospital communication including meetings and training sessions.

For Citizens Memorial, the biggest obstacle to home telehealth is the lack of insurance coverage. Davison confirms that, for now, home telehealth costs come largely out of the patient’s pocket, and that’s a customer service concern for patients who prefer to use insurance. “We’re still evaluating whether that’s feasible for the patient if they have an insurer,” she says.

Although telemedicine laws are still up in the air, the services can be hugely helpful to individuals without easy access to care providers. The service also benefits patients at multiple sites by bringing them together with one specialist—for example, diabetes education groups that can connect with diabetes educators remotely. “We have really made it a goal to be customer-focused,” Davison says. “Are there barriers to the patient in getting to a provider? We can facilitate that visit.” That involves patients coming into a Citizens Memorial office, where a nurse can take vital signs and facilitate the visit.

“Value Proposition”

The Mercy health system works with patients remotely through Mercy Virtual, which includes the Mercy Virtual Care Center in Chesterfield, Missouri—the world’s first virtual care center. Dr. Alan Scarrow, M.D., is the president of Mercy Springfield Communities. According to Scarrow, the service is currently serving patients in the Ozarks in various ways, including electronic intensive care units, where room cameras allow a specialist at the Virtual Care Center to keep an eye on patients by monitoring everything from vital signs to a patient’s pupils. They act as part of the care team and supplement local caregivers.

According to Scarrow, the rise of virtual care is related to a shift in the economics of medicine. “There is a shift from volume proposition, which relates to how many patients you see,” he says. “It’s shifting to value proposition, which is about how well you take care of your patients and at what price.” That starts with helping patients utilize the healthcare system less, particularly those who represent the “walking sick”—patients with chronic conditions who often average $150,000 or more in health care expenses. In the pilot stage of one project, Mercy Virtual served 12 patients in that category. They were given iPads with constant access to specialists and sensory devices to monitor vital signs. The program worked—it lowered the patients’ utilization of the healthcare system by 70 percent. Today, after expansion, about 65 patients in the Ozarks are using the system. There are about 310 patients enrolled across the Mercy network. Patients don’t pay to use the service. “It’s really about providing value for our patients,” says Sonya

Kullman, senior media relations specialist at Mercy. Kullman explains that Mercy is an Accountable Care Organization, or ACO, with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, which provides government reimbursement based on how well ACOs care for their patients.

Scarrow says the potential for growth is enormous. “This is just the very beginning of what we’ll be capable of doing,” he says. “We’re expanding about as rapidly as we can,” and he estimates that the number of Mercy Virtual patients will soon be in the thousands.